In an industry first, Nuro AI became the first American autonomous vehicle developer to be given exemptions for testing on public roads without the need to have controls for human operators. The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) decided to overturn existing rules that require drivers to have ultimate control of the autonomous vehicle and capped the top speed at 25 mph.

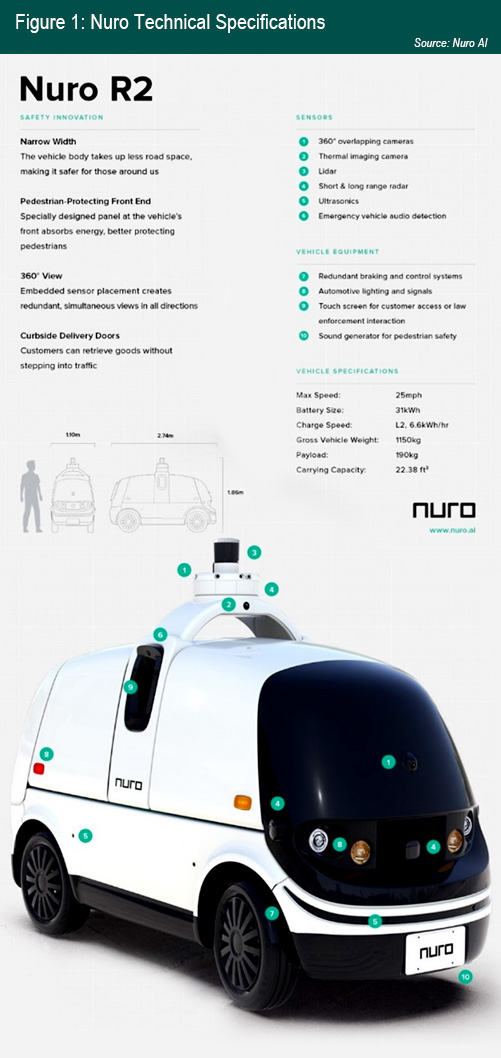

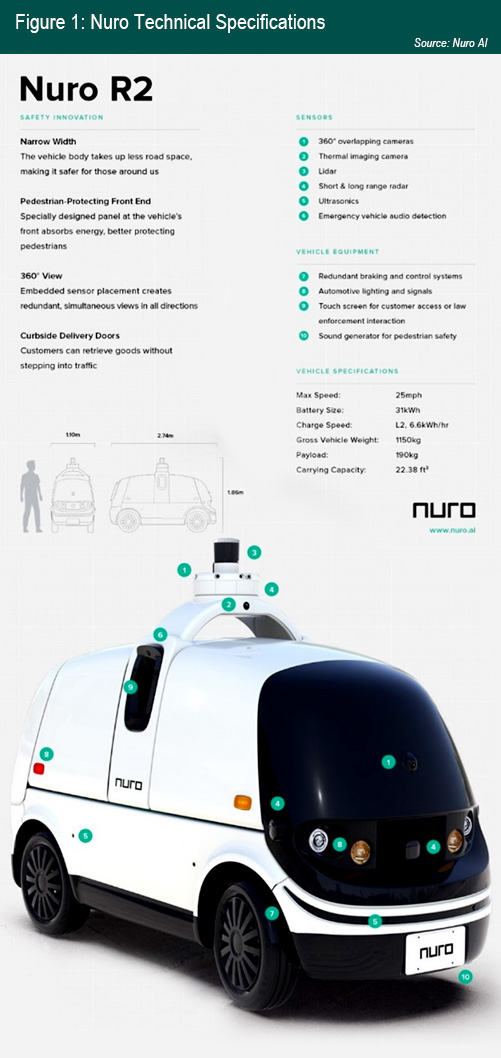

Nuro’s vehicle, the R2, builds on the company's R1 design for a container electric vehicle designed to transport and deliver groceries from Nuro’s end users. The R2 is scheduled to begin testing by the end of February and will join the fleet of Toyota Priuses that Nuro currently uses for autonomous vehicle testing. The R2 is a significant upgrade to the R1, weighing nearly twice as much at 1150 Kg to the R1’s 680 Kg and designed with a payload of 190 Kg. The R2 is advertised as an SAE Level 4 (highly automated) vehicle. Nuro states that, because the R2X’s Automated Driving System (ADS) relies on advanced Machine Learning (ML) to improve its level of safety, the R2X must be exposed to new driving scenarios. Nuro’s existing testing programs have consisted of operating its Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS)-compliant vehicle on public roads autonomously and operating the R2X in its private test track. Nuro argues that this testing has led to consistent improvements in the ADS’s driving performance, but that it has exhausted the safety gains it can accrue from its existing research and testing programs.

The exemption is a step in the right direction and an important milestone in the development of SAE 4 Level automation on the road, but not all test conditions were met by Nuro. Key test conditions, including fuel tank loading, driver’s seat positioning, steering wheel adjustment, and image response time procedure could not be met in light of Nuro’s passengerless or electric design. Modifications were tolerated and Nuro has convinced authorities that its autonomous driver system has built-in redundancies and that its sensor array is rugged enough to mitigate any issues. Overall, this development will be but a first step in the rise of last-mile delivery robotics. Nuro has relationships with Domino’s Pizza, grocer Kroger, and retail store Walmart. Under the exemption, which lasts two years, Nuro is allowed to produce and use up to 5,000 vehicles, but this is significantly more than the current fleet size. To compare, Starship Technologies (the leader in outdoor robot delivery), has under 500 robots and plans to have an installed base of 5,000 by 2021.

| |

|

|

The Reach of Softbank in Robotics

|

IMPACT

|

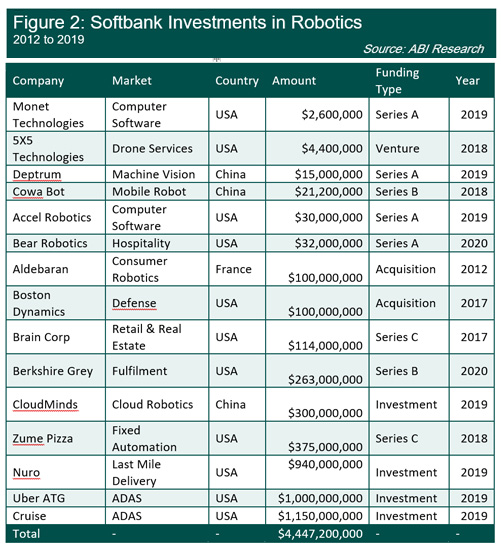

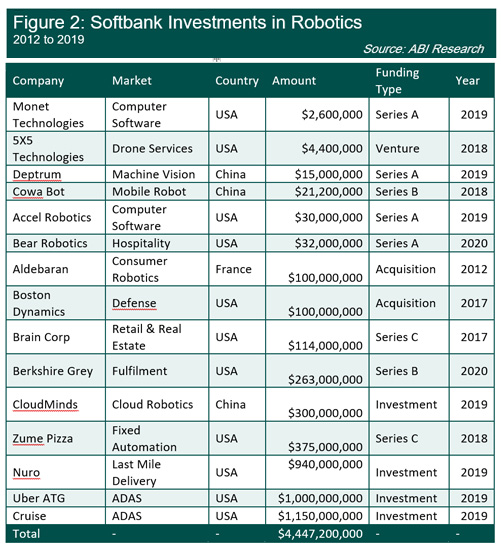

Nuro has made much progress and is a leader in the autonomous driving space as far as technology goes. While the California DMV has hundreds of permit holders for testing autonomous vehicles, the recent exemption and Nuro’s licensing of its software to other developers like autonomous truck developer Ike mark it out. Another key differentiator is that Nuro is backed, to the tune of US$940 million, by Japanese conglomerate Softbank. Nuro is far from the only robot-related recipient of Softbank’s largesse, as seen below. Through both acquisitions into Softbank Robotics and investments via the vision fund, Softbank has spent over US$4 billion on robot companies and adjacent technology developers in computer software.

| |

|

|

The year 2020 has seen two significant investments so far: one US$32 million investment in mobile hospitality robot Bear Robotics, which is being targeted for restaurants and casinos, and a significantly larger US$263 million investment in Berkshire Grey, which develops automation solutions for retail, e-commerce, and logistics fulfillment operations. According to Berkshire Grey, the new funding will help fund its global expansion, acquisitions, and team growth. The company’s robotics solutions aim to accelerate the transformation of customers’ logistics operations to address consumer expectations, labor shortages, and competitive pressures.

These two investments showcase Softbank’s continual excitement for the robotics oppurtunity, even in light of difficulties with previous recipients. Zume Pizza, which received US$375 million in funding in 2018, recently cut half its staff and switched completely from its initial focus on automating pizza production to developing third-party pizza delivery and packaging with the robots. The company is noted to have lost US$50 million and has been characterized by a lack of focus, although it retains the majority of Softbank’s funding. Furthermore, Pepper, the famous social robot developed by Aldebaran and acquired by Softbank in 2012, may have sold in large quantities, but has done little to push industry adoption forward, with many end users not renewing their leases of what is ultimately a gimmick.

Other cases are more nuanced. Artificial Intelligence (AI) solution developer CloudMinds has raised a reported US$317 million in total Venture Capital (VC) funding from investors, including SoftBank's Vision Fund, which holds a 34.6% share in the business. SoftBank previously participated in a seed round for CloudMinds and reportedly backed a US$186 million funding for the company earlier in 2019. The company has recently been in the news for deploying 5G-enabled robots for disinfection and medical delivery use cases in Wuhan and Shanghai, China in the aftermath of the Coronavirus outbreak. In addition, CloudMinds is affecting the robotics market with its enablement of data processing, advanced vision, and smart voice competencies for the future robot fleets to be deployed. The company logged a 2018 revenue of US$121 million but with a net loss of $156.8 million, compared to a 2017 revenue of $19.2 million on a $47.7 million net loss.

This is further evidence that short-term profitability is not high on the agenda and that Softbank is willing to take the long view on robotics. Unfortunately, similar bets with WeWork have likely failed. This hasn’t stopped Softbank from making an enormous US$1 billion investment in serial loss-maker Uber’s Advanced Technology Group (ATG). The ride-hailing company lost a staggering US$8.5 billion in 2019 and had to lay off 1,000 employees earlier in the year. While the company managed to increase revenue from US$11.3 billion in 2018 to US$14.1 billion in 2019, investors are increasingly becoming frustrated with its inability to chart a course to growth. Autonomy might be the way out of this gordian knot. In February 2020, Uber was granted a permit to test autonomous cars in California after suspending activity following the fatal killing of a pedestrian in Arizona in 2018. The ride-hailing company had remained testing in Pittsburgh and sees autonomous ride-hailing as the route to long-term profitability (the company hopes to turn a profit by 2021). Robo-taxis may help it get into the black, in that they get rid of Uber’s much contested compensation of its workers, but the idea of large-scale ride-hailing is unlikely to materialize by 2021. The hope to shift ride-hailing into an autonomous age is coming at a time when Uber is being constricted by ever-tighter regulations, including workers’ rights laws in California and losing its license in London. But the road to the automation of ride-hailing is itself strewn with regulatory barriers, and the idea that this can be scaled up by 2021 is fanciful. If autonomous robot taxis are Uber’s master plan to profitability, it will be a very long decade of maintaining the faith of increasingly impatient VC’s while fighting against the company’s deteriorating image in the eyes of activists, municipal authorities, and political parties across the ideological spectrum.

The pressure on Softbank’s beneficiaries is also felt by the company itself, which saw a US$2 billion reduction in profit in 2019. Many of Masayoshi Son’s own investors, including Paul Singer’s Elliott Management, are increasingly demanding greater discipline and stringency when it comes to making sure returns on investment are shorter than they currently are.

This is not to say Softbank has not also picked success stories. All the companies mentioned have impressive technology and most are reporting strong revenue growth. A particular outlier is Brain Corp, whose installed base of 6,000 autonomous sweepers stands out as the biggest deployment of autonomous commercial vehicles outside of manufacturing and logistics.

Softbank Is Scattershot, but Some of These Companies Will Pay Off

|

RECOMMENDATIONS

|

So, are the robot-related investments more akin to Softbank’s successful investment in Alibaba, or more like the investment in WeWork, with skyrocketing losses and misplaced hype leading to an abrupt crash? There are likely to be many casualties. The value of Pepper will deteriorate further, as the social robot oppurtunity is decidedly overrated in its value and will not have a significant impact in the near term.

The Zume Pizza investment is not being returned with the deployment of End-to-End (E2E) automation of pizzas. The prospect of using articulated robots for fresh food production was risky and has led to a significant pivot away from the initial high-tech focus and toward a more mundane proposition, with accompanying losses and a swift reduction in staff.

The ownership of Boston Dynamics could be rewarded with increased use for industrial inspection, but 2020 will tell if deployments for quadrupeds can be scaled beyond testing. Uncertainty is a common entity in the world of venture capital. When Softbank brought Boston Dynamics off of Google in 2017, the robot developer was exceptional for developing bipedal and quadrupedal robots (primarily for marketing purposes). Now, as it enters commercialization, there are some impressive new challengers in this space on similar trajectories and hoping to offer a low sales price, including Agility Robotics, Zoa Robotics, Ghost Robotics, and ANYbotics.

In terms of pure sunk cost, the key application for Softbank is autonomous driving. Exceeding US$3 billion, the investments in Nuro, Uber ATG, and Cruise may well offer strong returns in the long term but will likely require additional support and a wait of at least five years. Outdoor road-based autonomy suffers from huge technical and regulatory challenges. Nuro’s investment is of particular note because of the aforementioned exemption and because it offers a transformative platform. If Nuro can assure regulators that driverless vehicles with no manual operability can be allowed on the robot, the potential dividend is enormous. However, as stated, this is a long-term oppurtunity. Large automakers and tech companies have acquired and invested in self-driving startups to the tune of billions of dollars. If self-driving passenger vehicles are taken out of robotic investment calculations, the investment figures become much less impressive. But, while these big corporations understand the potential, they are by and large expecting this to be a very long and drawn out transition, a far cry from Google’s projections of driverless cars by 2009. Automotive companies are in fact likely to prefer incremental assistive automation over full autonomy because they don’t want to disrupt their positions in the industry.

The most promising investments are not the most experimental technologies (Boston Dynamics, Pepper, or Zume Pizza) nor the massive investments in self-driving road-based vehicles (Uber, Cruise, Nuro), but rather the mid-range investments in mobile robots for industrial and commercial applications, notably Brain Corp, Berkshire Grey, and Bear Robotics. Brain Corp has already deployed at an impressive scale and will likely expand on this with the rollout of Softbank’s Whizz bot (which uses Brain OS), while Berkshire and Bear have real potential to scale thousands of shipments without facing significant regulatory barriers or exorbitant upfront costs. While CloudMinds is operating at a loss now, it is well-positioned to serve the expansion of Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMR) fleets over the next two to four years and is already scaling up quickly. When determining where Softbank, and other VC’s, are likely to find success in robotics, it is mid-range investments in companies that can deploy mobile robots today.