Finland and the UK Pursue Contactless EMV

|

NEWS

|

The Finnish city of Hämeenlinna has enhanced the experience of its public transport users with the launch of contactless EMV (the standard smart payment card) payments.

With approximately one million passengers using the bus routes annually, the city has seen ridership drop to under 70% of usual levels, forcing the transit authority to consider incentivizing public transit to encourage ridership to return to pre-COVID levels. After Helsinki, Tampere, and Oulu, Hämeenlinna is now the fourth Finnish city to offer contactless EMV fare collection on its public transport network. Furthermore, they are the latest in a significant number of TAs (Transportation Authorities) to introduce a PAYG (Pay as You Go) fare-capping system, having integrated a system in which travelers paying by contactless EMV can take advantage of a 90-minute window to tap-to-pay with unrestricted bus switches.

Similarly, the United Kingdom (UK) Government intends to install 700 rail stations that will accept contactless open-loop payments aiming to echo the success of the contactless pay-as-you go fare payments system of TfL (Transport for London). Aimed primarily at the North and the Midlands, the objective, similarly to Finland, is to upgrade towards a fare capped contactless PAYG system. Having already reintroduced fare caps on Oyster, TfL is now fare-capping across the board in an incentivization program to reintroduce travelers back to public transport.

Across the world, the ticketing ecosystem is seeing a trend heavily shifting away from monthly and annual passes and towards a PAYG fare-capped model as riders are understandably hesitant to commit to a longer-term pass which could be cut short as transit networks open, close, and restrict services under the effects of the ongoing COVID pandemic.

Ridership Reductions Across the Globe

|

IMPACT

|

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the social-distancing measures introduced by governments across the world, had a detrimental effect on global transit networks. Unable to operate services at maximum capacity, as well as a push towards contactless experiences in all areas of citizens lives, made it unfeasible to fill carriages and offer the level of services typically seen in pre-pandemic times. This was only compounded by mandatory work-from-home instructions and complete closures of entire sections of the public transport network. As a result, citizens travel habits had to change and adapt to the new normal, with many electing to walk, bike, or car share in order to travel. This leaves the question: once the pandemic has been largely managed and services are running at maximum capacity, how much of the ridership base will return to the transit network? As mentioned above, TAs have been quick to incentivize a return to transit networks, with an emphasis on contactless EMV rollout augmented with fare-capping. But for those that have left the transit network, and now favor alternative transport methods, it is likely they may never return to the transit network no matter the incentive, and the plateau of ridership may never recover to what it was before.

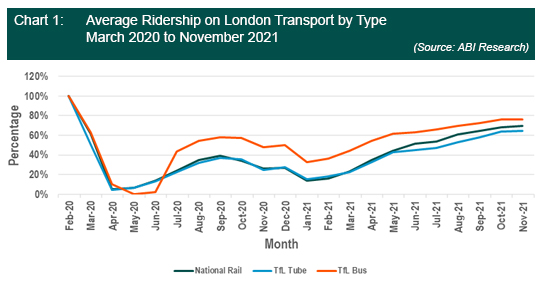

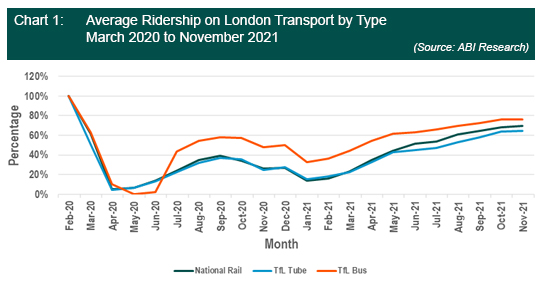

The UK, having rollout double vaccinations, undertaken a booster program, and been through the worst of the COVID waves, has practically returned to normality as it relates to transit network service levels and capacity. However, as can be seen from the graph above, neither National Rail, TfL Tube, or TfL Bus have returned to the 100% ridership levels they experienced pre-pandemic, and indeed look to have plateaued at between 60-80%. Of course, in the very long-term, net new travelers entering the ecosystem will see ridership numbers recover to pre-pandemic levels, but at the present, a significant portion of London’s ridership have found a new way to travel or are simply not traveling altogether.

This presents a significant problem to TAs, with the worst lockdowns in European countries lowering public-transit ridership to 10-15% percent of the typical level. As the world progresses slowly towards a post-COVID age, transit authorities must somehow champion ridership increases to help drive an economic recovery without compromising public-health measures and risking another recurrence of the virus. They must also consider how to tackle the financial losses that the ridership downturn, which is not looking to end any time soon, will continue to bring. As it relates to regions:

- In Europe, public transit demand has experienced a good recovery, with ridership recovering to approximately 60% of typical levels. While infection levels remain very high in countries such as the Netherlands and the UK, advanced vaccination programs are enabling transit networks to grow in ridership and service offerings.

- In the Asia-Pacific region, while not initially hit hard by COVID cases and restrictions in early 2020, the effect was felt later in the region with rapidly rising outbreaks in Taipei, Bangkok, Singapore, and India causing strong downturns on ridership between March and April 2020, then again in April and May 2021. In August 2021, average ridership for the region decreased to 50%.

- North America, while initially seeing the largest decrease in ridership in April 2020 to under 10%, recovery through 2020 and 2021 has been slow but steady, though at around 30% this is still the region with the lowest ridership levels globally. It will be a significant issue for TAs to overcome to recover lost profits if riders cannot be enticed back to the transit network.

- Latin America is on a similar path to that of North America, though the drop in overall ridership was less severe through the worst months of the pandemic. Decreasing to around 20% of typical ridership in April 2020 and now steadily increasing past 45-50%, the return of ridership has been slow and steady, yet still far below Europe and the Asia-Pacific in terms of a recovery.

White-Label EMV Becoming More Prevalent and Competitive

|

RECOMMENDATIONS

|

With TA’s looking to contactless EMV and fare-capping as a way to reintroduce travelers to the transit network, there is still the presence of an alternative to consider; closed-loop EMV, otherwise known as “White-Label EMV”. The drive towards providing travelers with more and more choices of fare media with which to make payments has brought attention to white-label EMV cards in place of proprietary closed-loop cards for riders who do not have or do not wish to use their contactless payment cards for transit.

A number of key TAs are eyeing the potential of white-label EMV with others already having launched or in the process of launching such a system. New York and Stockholm only in the last few weeks have rolled out their white-label EMV system, with TfL set to follow in 2025, and Sydney’s Transport for New South Wales considering a similar move for their respective Oyster and Opal cards. California is undergoing arguably the largest transition to a state-wide white-label EMV system, which will see the state’s 300+ transit agencies move to open-loop payments.

The new model of white-label EMV differs from previous implementations such as the Chicago Ventra card which took the form of a prepaid EMV fare-card. While Ventra operated a separate closed-loop transit purses attached to an open-loop prepaid EMV card, it struggled to get off the ground and, after migrating to a digital Ventra card, Chicago ended the Ventra card altogether.

While white-label EMV is a tempting solution for TAs, it would cause a set of new problems for long-standing and well-established closed-loop offerings such as MIFARE and Calypso. While closed-loop proprietary cards boast a faster gate-speed and command a lower Average Selling Price (ASP) for TAs to issue, white-label EMV backers are suggesting the solution is becoming more accessible from a price-point perspective, something which will give TA’s across the globe plenty to consider moving forward.